U.S. President Donald Trump wants Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to come up with a plan to grant the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina what he calls “long overdue” federal recognition, fulfilling a campaign promise he made last September.

Federal recognition acknowledges a tribe’s historic existence and its modern status as a “nation within a nation” entitled to govern itself and receive federal benefits, including health care, housing and education.

Historically, tribes were recognized through treaties or laws or presidential orders or court decisions. In 1978, the Department of the Interior standardized those procedures, allowing recognition through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Congress or a federal court ruling.

Those standards require tribes to demonstrate continuous political autonomy since the 19th century, and members must document descendance from historical tribe members.

The process is time-consuming and expensive, often requiring assistance from historians, genealogists and attorneys. Historic records, if they ever existed, may be lost or destroyed.

The 1978 rules, updated in 1994, also state that tribes previously denied cannot reapply.

‘Gray eyes’

Over time, the Lumbee have been linked to several historic tribes, including the Cheraw, Tuscarora and even Siouan tribes.

“One tribal name or a single cultural origin is insufficient to explain Lumbee history, because Lumbee ancestors belonged to many of the dozens of nations that lived in a 44,000-square-mile territory,” writes Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery. “The names of these diverse communities varied depending on where the people lived and on what Europeans wrote down about them.”

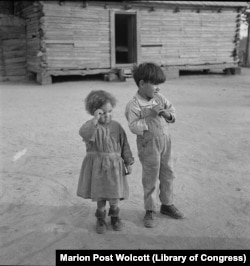

In 1584, English explorer Arthur Barlowe noted that some Indian children on Roanoke Island had “very fine auburn and chestnut coloured hair.”

Three years later, England established a small colony on the island. The governor left for England to gather supplies. When he returned, no one was there. There were two clues: the word “CROATOAN” carved into a fence post and “CRO” on a tree. This gave rise to the theory that they had been taken in by Croatan Indians.

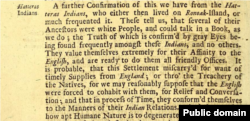

In the early 1700s, Hatteras Indians at Roanoke, as the Croatans were now called, told English explorer John Lawson that they descended from those vanished settlers. They also had “gray eyes,” which Lawson believed confirmed their mixed heritage.

“They tell us, that several of their ancestors were white people, and could talk in a book [read], as we do, the truth of which is confirmed by gray eyes being found frequently amongst these Indians, and no others,” Lawson wrote.

Enduring names

The 1790 federal Census recorded family names found among the Lumbee today and classified them as “all other free persons.”

In 1835, North Carolina banned voting in state elections for anyone who had a Black, mixed-race or biracial ancestor within the past four generations, and the state amended its constitution to segregate Black and white children into separate public schools.

“As the lines between ‘white’ and ‘colored’ hardened in North Carolina … Indians resolved that non-Indians must recognize their distinct identity,” Lowery wrote.

In 1885, North Carolina recognized the Lumbee as “Croatan” Indians and created separate schools for them. Shortly after, 54 members identifying themselves as Croatan Indians and “remnants” of the lost colony petitioned Congress for aid to educate more than 1,100 of the tribe’s children.

The Indian Affairs commissioner turned them down, saying he could barely afford to support the tribes already recognized, let alone the Croatans.

The tribe renamed itself “Lumbee,” after the nearby Lumber River, in 1952. In 1956, Congress passed Public Law 570, acknowledging the tribe as a mix of colonial and coastal-Indian blood but denying them federal benefits.

In the 1990s, the Interior Department again rejected the Lumbee’s petition, citing insufficient proof of cultural, political or genealogical ties to a specific historic tribe. Despite failed bills, the House passed the Lumbee Fairness Act in December 2024, which, if approved by the Senate, would grant federal recognition and benefits.

The Interior Department released an update to the acknowledgment process, allowing certain tribes that were previously denied the opportunity to reapply for recognition. That was set to take effect this week but has been postponed to March 21.

Congress ‘not equipped’

North Carolina’s federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) has long opposed Lumbee recognition.

“The Lumbee cannot even specify which historical tribe they descend from, and recent research has underscored the dangers of legislative recognition without proper verification,” EBCI principal chief Michell Hicks said in a December 2024 statement. “Allowing this bill [the Lumbee Fairness Act] to pass would harm tribal nations across the country by creating a shortcut to recognition that diminishes the sacrifices of tribes who have fought for years to protect their identity.”

Former EBCI chief Richard Sneed told VOA in 2022, “Congress is not equipped to do the necessary research to determine whether or not a group is a historic tribe or not. The process was created for that purpose.”

In an emailed statement, Lumbee tribal chairman John L. Lowery expressed cautious optimism that the Lumbee Fairness Act would pass.

“Our critics are sad individuals who use racist propaganda to discredit us while ignoring the struggles of other minorities in America,” he told VOA. “As Indigenous people, we are the minority of the minority here in the United States, and our critics are trying to erase the memories of our ancestors, and we will not let that happen!”

Fifty-six thousand people identified as Lumbee in the 2020 U.S. Census. If recognized, they would be the largest acknowledged tribe east of the Mississippi River.

![“A chief lord of Roanoac [Roanoke]" from Theodor de Bry’s Engravings for Thomas Harriot’s Briefe and True Report (1590).](https://gdb.voanews.com/9de27047-b11f-4db2-f7b5-08dd4a817620_w250_r0_s.jpg)